|

You may have gripes about the occasional distastefulness of the news media, but you would feel

cut off from humanity if the news media ever went away. Interference with the news media (extended interference) would leave whole communities vulnerable to panic-mongering

and unscrupulous manipulation.

Television and radio news broadcasts must be viewed and treated differently than the traditional "press" communications. Unlike the news in print, or even on the Web, TV and radio news broadcasts can trigger masses of people to mobilize instantly, for better or worse. As such they deserve at least as much protection from mischievous interference as the 911 system. Those two channels of "the press" -- TV and radio news -- are what really protects and serves and reassures us all, around the clock.

Deception schemes can mislead news broadcasters into reporting false information. That is a form of interference, because news broadcasters do not want to report false information. They want to report reliable information.

Hoaxes (i.e. deception schemes) are already prohibited in the context of law enforcement investigations, and when gaining access to federal property, and during military actions, and during business transactions. Deception schemes are outlawed in those contexts for a long list of reasons. Among them: To protect the public, and to prevent chaos. Legal penalties, in those contexts, undoubtedly help reduce their occurrence.

There is no legal penalty for deception schemes in the context of news broadcasts. Deception schemes should be outlawed in the context of news broadcasts, for a list of reasons. Among them: To protect the public, and to prevent chaos.

The Parameters of a Proposed Statute

Hoaxes utilizing the news media would not be considered a crime against the public, but rather a crime against a given broadcaster. Only a federally licensed/registered broadcaster would be able to invoke the statute against someone.

There would be statutory damages against all perpetrators. Some damages would be payable directly to the broadcaster victim. This would allow a news broadcaster to receive compensation more quickly, without having to prove actual damages.

There must be both criminal penalites and a high statutory damage amount, to ensure the penalties will never be calculated as an acceptable, absorbable cost of doing business, perhaps for a well-funded marketing/publicity campaign, or a more subtle profiteering scheme.

The statute would be similar in certain respects to the existing "Wire Fraud" statute, but without the requisite elements of a specific victim being intentionally defrauded for money or property. A hoax may not require those elements, yet may still be very profitable in various ways -- ways which may be difficult to identify or quantify until long after the fraud has been perpetrated.

The constitutional policy rationale should be supportable under various constitutions, not just American, so the American statute can serve as a model for other countries ... like Canada.

The framers of the American Constitution believed the news media should be protected

from interference by the government. It was one of their guarantees of

free speech.

Their position was expressed as a prohibition against any law that

"abridges the freedom of the press." Logically the framers would

have disapproved of any party, not just government, being able to abridge the freedom of the press.

The framers could not have foreseen how the electronic press

would become the pillar of infrastructure and business that it has become,

and how the *instantaneousness* of the transmission of news stories ... would make the news media both

attractive and vulnerable to interference and manipulation by non-government actors,

for the purpose of private gain.

Hoaxes occurred in the Constitutional Era as well, but their impact was

different when the press was only in print; not spread instantaneously

to millions of people. News stories in that era had more time to cook

before circulation, allowing more time for the truth to emerge before

people were called upon to mobilize.

A modern Supreme Court decision related to the freedom of the press

arose from a situation where a state government tried to compel (by invocation of the Fairness Doctrine)

a newspaper to write particular stories rather than not write particular stories.

Injecting stories into the press by legal compulsion was eventually considered an

unconstitutional "abridging" of the freedom of the press.

If it is illegal for a government player to inject stories into the press by court order,

then logically it should be illegal for any player to inject stories into the press by

trickery.

The proposed statute would provide protection from interference by non-government entities, as a natural extension of the Constitution's protection from governmental interference.

A criminal penalty will not completely prevent hoaxes

from being attempted, but it will make it much more difficult to recruit assistants.

Elaborate, convincing hoaxes are much more difficult to pull off without a team.

None of the recent major news hoaxes would have gone as far as they did without a team effort. In some cases the team's job was just to stand around and corroborate the story, to make it all seem legitimate for as long as possible.

At present a con man can persuade certain types of guys and gals that there is no risk at all in assisting with a hoax on the media. Certain types of guys and gals have nothing to lose ... Plenty of them can be persuaded that the big bad media is partly to blame for their unhappy situation. A con man can persuade those flexible types that there could be decent money in it for them, within a matter of days, if everything goes as planned, and there's no risk of going to jail for trying. And it might not be a lie.

The proposed statute should be made law before a large organized hoax comes out of nowhere and triggers a chain reaction of panic in the financial markets.

A large organized hoax would have the greatest potential for deception, and the greatest potential for harm, and the greatest potential for an extended interference with the broadcast news media. Enactment of the statute would likely succeed in detering any large, organized hoaxes.

Unfortunately the Wire Fraud statute does not apply to hoax cases like "Balloon

Boy" in Colorado, because that scheme did not yield (nor even require)

a specific victim to be tricked out of money or property,

or a legal right. Without those elements there was no "conspiracy

to commit wire fraud" either.

Heene may have taken money for interviews following the incident, but that

was not wire fraud because he was not being paid to tell the truth; he was

merely being paid to appear and talk on camera, and he did.

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Celebrity wannabe Richard Heene used his family in a wreckless hoax

calculated to bring him notoriety and entertainment deals based on

that notoriety.

At its core Heene's hoax was not illegal. The criminal liability stemmed

from his false statements to law enforcement officers, not his false

statements to reporters, and millions of TV viewers.

|

|

| |

|

|

Heene was later charged with a felony for making false statements

to law enforcement officers (and other public officials) ... but

not for hoaxing the press and the public. That part was permissable, and

that's why it happens. You can get away with it. There is no real punishment.

Fear of shame and infamy is no deterrent to some people. Hoaxers are often

desperate people who have no good reputation to lose. They have only some

hope that dubious fame might bring them somewhere better.

Some suggest the news media is partly to blame when they fall for hoaxes

by these types of people, either because the news people should have investigated

the matter more thoroughly, or they simply should have known better. But

blaming the news media for these situations is like blaming the victim.

It also reveals some unfamiliarity with the electronic news gathering process.

Nowadays, news directors make quick decisions about whether to go live to

a breaking news story. On occasion, unscrupulous people will take advantage

of that ... especially if it is perfectly legal to do so.

The potential for this conduct goes up whenever a belief begins to take

hold among misguided people that attention and fortune can be gotten quickly

that way ... if all else fails ... and there are no bad consequences when the ruse finally unravels.

The news media in general tries to avoid stories, rumors and characters

that do not appear to be credible. They definitely do know better

most of the time. The few hoaxes that make it all the way to live

breaking coverage on all news channels are the scams that wiggle through

the net. It happens, and will happen, periodically when a scam is novel,

sensational and elaborate ... and the scammer is a persuasive conman, or

a pretty good actor.

Richard Heene upset many people for a list of reasons. The viewers who became

glued to the story on live TV thought they were witnessing a tragedy. A

few days later when it became clear that it was a hoax, people felt highly

offended, and rightfully so. It was more than a publicity stunt. It was

a publicity scheme that misused the news media, the public, and law

enforcement, as it exploited the strong concern and focus that humans always

have for a child in imminent physcial danger.

Tom Biscardi's "Dead Bigfoot hoax" in 2008

angered many people also, but it did not cross the same line as the Balloon

Boy hoax. Although one of the perpetrators was a sheriff's deputy, the dead

bigfoot was never reported to a law enforcement agency by any of the three

perpetrators, so there was no false police report involved. There was no

apparent crime to investigate otherwise (perhaps just a civil lawsuit),

and no public safety concern, so law enforcement did not get involved at

all.

Biscardi had years of experience structuring cons in ways that allowed

him to avoid accountability and prosecution. He knew to avoid making any

statements to law enforcement officers along the way.

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Charismatic Carmine (Tom) Biscardi chats with Foxy reporter Megan

Kelly about the dead bigfoot he claimed to have examined in Georgia.

He used this live appearance on Fox News to announce an upcoming press

conference that would "shock the world". Click the image

above to see the video.

It seems odd that a person can be jailed for lying to a single law

enforcement officer, but if a person weaves a tapestry of lies for

TV reporters in order to deceive millions of people simultaneously

... that's perfectly legal. |

|

| |

|

|

At the same time he could spout outlandish lies and misrepresentations

to anyone in the media, even on live national news broadcasts, with no

consequences, except for acheiving the status of a "controversial

television figure" ... For some men that status is much more fulfilling

to their egos than the feeling of being a lonely, discarded failure.

Richard Heene was probably familiar with Biscardi and the Dead Bigfoot

hoax. He probably followed the story enough to know that a sheriff's deputy

was involved in that case, and a few people made a few thousand dollars

off it, but no one went to jail.

The absence of criminal prosecution in Biscardi's case may have contributed

to Heene's decision to perpetrate his own hoax.

You may think it would be difficult to devise a convincing, sensational

hoax that can avoid law enforcement completely.

In fact ... most of the famous hoaxes of the past avoided law enforcement.

But there's an issue of semantics here. When a "hoax" triggers

some criminal liability ... it is generally not referred to as a "hoax"

anymore. It is referred to as a "fraud," or a "scam,"

or "hustle," or "con job," etc., from that point foward

(there are exceptions, like Balloon Boy).

A "hoax" is understood to be an elaborate practical joke, or

harmless manipulation, that fools a lot of people and gets a lot of attention.

Criminal charges tend to transform the perception

of harmlessness.

Photo hoaxes on the Internet are too numerous to count, but that's exactly

what reduces their potential for mischief -- people are used to them by

now. The news media doesn't pay them attention anymore. Literary hoaxes

are still relatively common, but they attract little attention because

their context (literature) is mostly fiction anyway.

Archaeology hoaxes are less common, but have been happening

for years. They tend to attract more news attention than literary

hoaxes because people generally trust the integrity of archeologists.

Every so often a sensational "science hoax" appears out of nowhere

like a meteor and shines brightly in the news media for a while, attracting

loads of attention. Science hoaxes have a long

history and can be expected to occur again in the future. Science

hoaxes rarely trigger the involvement of law enforcement.

We all generally agree that law enforcement should not be deceived with

false reports, or interfered with unnecessarily, or used inappropriately,

because they provide vital services to the public. But TV news and radio

provide vital services to the public also ... services which are no less

vital because the organizations are are privately owned. Those services

should not be interfered with, or used inappropriately, either.

Would the Statute be Unconstitutional?

Some will argue that a statute prohibiting hoaxes on the news media would

actually contradict the beliefs and intentions of the framers of the Constitution,

because it would be a new law that limits freedom of speech in some respects,

but this is more of a context issue than a content issue.

We all relinquish some of our rights to freedom of speech in a long list

of contexts already:

- You are not allowed to falsely yell "Fire!" in a theatre.

- You are not allowed to make terrorist threats to your neighbors.

- You are not allowed to write a letter saying there is anthrax in

the envelope.

- You are not allowed to "cry wolf" about a military aggression.

- You are not allowed to threaten to spit in the president's face.

- You are not allowed to joke about having a bomb on an airliner.

- Etc, etc.

Relinquishing your rights to certain types of speech in certain contexts

... is a good thing. We could certainly add another reasonable item to

that list without feeling politically oppressed:

- You cannot perpetrate a hoax on broadcast television news or radio news.

Broadcast news organizations are important community resources,

even though they are privately owned. They provide a public service called

"electronic news gathering" (ENG).

ENG collectively protects

and serves and reassures the public, around the clock. ENG also reassures

and stabilizes the same business environment that the Wire Fraud statute

was designed to protect -- the environment that maintains the value of

our currency.

The law should protect any important community resource from being

deceptively misused for private gain.

If we demand high standards from news people, then we should also demand

high standards from those who provide information to news people.

The news media in general endeavors to maintain the highest standards

of credibility because there is some accountability if they don't.

The threat of negative consequences, in some real form, should apply all

the way through the chain of electronic news gathering, not just at the

final links of the chain. Any person who intentionally pours non-credible

information into that vital stream should bear some sort of accountability.

The interconnected, national reach of the news media requires the statute

be a federal law rather than a state law. There can be no safe-haven states

where hoaxes can occur legally, and then be transmitted to other states

-- the same logic that made wire fraud a federal crime.

The Wire Fraud statute was an expression of a rationale among legislators

that they must prohibit wire fraud because it is bad business. Bad business

interferes with good business.

The Wire Fraud statute must exist in order to facilitate good business

and protect public confidence in the business environment. By extension,

a statute prohibiting hoaxes on the news media must exist to facilitate

legitimate news and protect public confidence in the national news media.

Would an anti-hoaxing statute open a can of worms?

Would an anti-hoaxing statute discourge people from speaking to journalists,

for fear they might be prosecuted later if their statements turn out to

be inaccurate? Would it have a "chilling effect" on political

activism, or artistic expression?

No, no and no. The language of the statute could limit its application

to fraudulent schemes directed at TV and radio new

outlets, rather than just false statements to journalists. Making this

distinction clear in the statutory language should not be terribly difficult. Balloon Boy, Dead Bigfoot, etc., are very different animals than mere statements to journalists. A hoax is very different thing than, for example, denials about an extramarital affair, or a pattern of misrepresentations

in political speeches, or mislabeled artistic performances. The terms

of the statute can narrowly define the conduct and context so that the new law cannot be misapplied to scenarios for which it was not intended.

Where do you draw the line?

The statute would not outlaw hoaxes in every context. In fact, it would

not outlaw hoaxes in most contexts. Hoaxes on YouTube, or in newspapers,

for instance, would not fall within the scope of the statute.

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

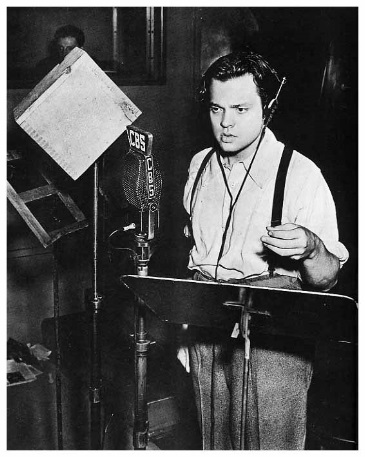

Orson Wells would not have violated the proposed statute

with his "War

of the Worlds" radio drama in 1938. The drama was hosted by a radio

broadcaster, so therefore it was not a deception against

a broadcaster. It wasn't an intentional deception either ... or

so they claimed. They did announce it as a dramatic performance ...

There were three (3) disclaimers -- before, during, and after the hour long program --

clearly stating that it was only a dramatic performance, rather than a

real news bulletin. However, this long radio drama ran without commercial breaks

for the first forty (40) minutes ... hence zero (0)

disclaimers during that 40 minute gap ... 40 minutes of uninterrupted,

authentic-sounding, emergency news bulletin on the public airwaves,

back when people were accustomed to hearing only reliable news bulletins on the radio.

Many listeners tuned in from other radio stations during that 40

minute gap and thought they were hearing an authentic bulletin about a doomsday scenario -- creatures from outer space were invading the Earth.

A significant numer of people across the country panicked. Many began communicating news of the alien invasion to their friends, neighbors, and relatives. The story

spread quickly through various channels, but without the important

disclaimer that it was only a drama ... and it triggered a chain reaction of public panic on Halloween night, 1938 ....

In retrospect, at least, it was a rather unsafe thing to do,

in

a country full of guns and booze, and on a night when some folks were bound to be surprised by strange looking creatures knocking on their doors.

Luckily, no trick-or-treaters were hurt, but lots of people were fuming the next day. The panic caused by the drama became a front page news story in itself, and young Orson Wells became a household name.

Eventually various immitators figured out new, clever ways to trigger a chain reaction of panic using the broadcast news. None of those hoaxers was ever prosecuted, because there was (and still is) no law specifically prohibiting hoaxes in broadcast news reports.

|

|

Broadcasters should not be allowed to invoke the statute on each other.

There might be some temptation to do so for competitive purposes. Any

federally licensed/certified broadcasters (covers both cable and airwave

transmission) must be exempt from liability under the statute. The FCC

would need to police and punish broadcasters' misdeeds against each other,

as they can do at present. It would not be loophole of the statute.

The prohibited context for hoaxes (schemes based on deception)

would be where the deceptions are directed at federally licensed/certfied

broadcasters that can, and do, transmit live news in a linear stream

to the public. This is the context where hoaxes should not occur.

A given TV or radio news organization might also have Internet,

print, text messaging, etc., arms of their operation, but a violation

of the statute would only stem from direct false reporting

to TV news and/or radio news arms of the operation (think

Balloon Boy and Dead Bigfoot) ... i.e. not an entertainment arm

of the media operation, and not the talk radio arm of a media

operation, and not the news website arm of the operation.

So fiction and humor and hoaxes, etc., could still legally happen anywhere

in print and anywhere on the Internet, because in

those contexts hoaxes do not interfere with legitimate news reporting

quite as much.

There is simply not as much potential for interference with the press

wherever people must actively pick and choose which news stories they

want to read, or watch, or listen to. Whereas, the linear transmittal

of broadcast TV and radio news has the potential to redirect national

attention and concern away from things that should reasonably receive

more attention and concern.

Of course, people can choose to not watch TV when there is a live

breaking news story somewhere, but people need to be able to switch

on the TV news, or radio news, at any time, to connect with the larger

world and find out the worst things that are bubbling up. They

also need to ascertain if they need to worry about anything in their immediate

environment or community.

A sensational breaking news story on TV or radio has the potential to

suck in extended live coverage from every broadcast news channel

(even those on cable TV). That severely interferes with the transmission

of legitimate news on those channels.

If news broadcasters are trying to only put forth legitimate news,

and unscrupulous people can deceptively redirect those channels to some

fake news, legally, then the law permits any non-government actor

to interfere with the press, in effect.

At present, a person or company can legally plan and execute a clever

hoax on the new media (if they can avoid the involvement of law enforcement)

for the purpose of directing national attention away from something

else. They can potentially direct focused national attention on a bogus

event, in order to reduce coverage on something they may want to be off

the public radar screen for a few days, which may be all they need

to cash in somehow.

Other scenarios:

1) In the future a juvenile may put himself in a runaway balloon for his

own juvenile publicity purposes, perhaps believing that he can save his

family from financial peril if lots and lots of people will send them

donations as soon as his harrowing ordeal has ended, one way or another.

2) In the future another disgruntled government employee may damage the

credible reputation of his office by committing a harebrain hoax, in order

to win public sympathy for himself, or donations, or a reality show deal,

or the sale of bogus photos or artifacts, etc., etc.

Americans are amazingly creative in using all their available legal

rights in the course of their entrepreneurial experiments. Other would-be

entreprenuers pay close attention to see which gimmicks work and which

don't ... and which gimmicks are painful and which are pain-free.

Who draws the line? Who is punishable? Who is the victim?

Those who must be exempt from liability under the statute:

Broadcasters would need be to exempt from liability under the statute,

for practical reasons, and because they are already accountable to, and

policed by, the Federal Communications Commission (the FCC).

The proposed

statute is intended to provide deterence and accountability where it currently does not

exist. It should not provide *additional* liability and deterence where it already exists.

Deterence and accountability already exists if the perpetrator is another broadcaster. Likewise, it already exists if the perpetrator is a government agency, or department, or a government employee acting upon orders from a government supervisor.

There is real accountability if the perpetrator is a government player, and there are civil rights violation remedies if the case negatively impacts civilians.

One of the perpetrators of the Dead Bigfoot hoax was a government employee, but he was not acting upon orders from a government supervisor. That's why "government employees," per se, cannot be exempt from the statute, but more specifically government employees acting upon orders from a government supervisor.

Broadcasters should never have the right to compensation from the government if they report false information furnished by the government. That would be a can of worms.

There are times, for example, when law enforcement officers will intentionally inject false information into the media during the course of a kidnapping or hostage situation in order to precipitate some action or inaction. LE officers should never have to worry whether a strategic charade for the cameras can be used against them later by a broadcaster.

Various forms of mischief can occur if journalists (who are not all angels) can threaten invocation of this statute against government employees

in order to get more information from them, or more attention to their story.

A survey of broadcast executives would undoubtedly demonstrate their sense that sensational hoaxes are far more likely to emerge from a non-government entity than a government entity, so exempting government from civil/criminal liability under the statute would not make the statute toothless, because that is simply not where the major threat comes from.

What if someone reports a situation to broadcasters without knowing it's a hoax?

A hypothetical scenario will help us explore the tricky issue of who is punishable:

A local bigfoot research group in Michigan obtains some sound

recordings near a river. They put those recordings on their Internet web

site, along with their notes about how the recordings were obtained. They

also state their strong belief and interpretation that the sound recordings

are authentic sasquatch sounds.

A few days later a different person(s) reads their web site and forwards

the information to a local TV station, which then goes out and does a

news story on the sound recordings, suggesting they may be legitimate.

Then yet another person steps forward to allege that the sound recordings

were a hoax, and this same person implicates the local bigfoot research

group. Does that provide grounds to investigate the local bigfoot research

group for a federal crime?

What if it can be demonstrated that the recorded sounds were earlier recordings

from a different part of the country -- authentic sasquatch recordings

that must have been broadcast from a loudspeaker from across the river,

and thus someone actually did perpetrate a hoax ... but the hoax was,

in reality, directed at the local bigfoot research group, and not

perpetrated by the bigoot research group? Should there be a federal

investigation in that scenario to identify and prosecute the real

hoaxers?

No, no and no. Only if a hoaxer directly pushes the deception into TV

and radio channels by either contacting the news media directly, or the

hoaxer(s) sets in motion a series of events that would normally lead to

TV and radio media attention, and then the hoaxer(s) continues

to deceive journalists with the bogus story, and explicitly denies the

deception to the TV and radio news organizations (e.g. Balloon Boy and

Dead Bigfoot).

In other words, a hoax that would otherwise be legal would not become

a federal crime if it eventually made its way to TV and radio news channels

... not unless the circumstances clearly demonstrated an intent

to make that happen by continuing with the deception once it began to

receive TV and/or radio news coverage.

Thus, if the news media inteviews the Michigan group about the recordings,

and that group continues to express their belief that the recordings

are authentic, but they are honest about the circumstances, and they do

not deceptively claim that they actually watched a sasquatch make the

sounds they recorded, but rather merely recorded them from across the

river, then there is no deception involved, because it is logically obvious,

up front, to everyone concerned, that a third party hoaxer might

have blasted those sounds from across the river. The group can rightfully

maintain their own innocence if they accurately present the facts of the

case.

But what if some person among that group is secretly in cahoots with the

hoaxers on the other side of the river? Does that put the spokesperson

for the group at risk ... if he/she was truly deceived as well?

No, neither the spokesperson for the group, nor the other group members,

would be at risk because as with all criminal prosecutions there

would need to be evidence of intent to commit the crime (regardless

of whether the perp(s) knew it was a crime or not). The intent to do

the deed is the important thing. It might not be evident at first,

but would arise later, and would need to arise first before

there were any grounds to press charges against anyone.

Evidence of intent eventually bubbled up in the Balloon Boy case, and

in the Dead Bigfoot case, and can be expected to bubble up in any other

hoax case.

If there is nothing logical nor evident to suggest that a false

alarm was anything other than an honest misinterpretation of

a situation ... then nobody would suggest a hoax in the first place ...

When there is a federal lawsuit alleging interference with a news organization

by a government entity, the news organization is claiming to be the victim

of the interference. The law does not consider the public to be

the victim (as it often does with "victim-less" crimes like

gambling, public intoxication, wreckless driving, etc.). If a news organization

does not claim it was interfered with (by any type of government agent

or department) then no one else can make that claim for them. In the same

way, a news organization would claim to be the victim of a hoax scheme,

before charges could be brought against a hoaxer. Charges could not be

brought by a member of the public who felt deceived or offended. That

would open a can of worms, indeed ...

It would always be a hassle, and a waste of news provider's time and resources,

to help bring criminal charges against a hoaxer. That's the built-in

procedural mechanism detering any flippant use of the statute. The news media

would only bother to press charges in the most egregious cases, where

they are very upset by a hoax. For example, if a hoaxer deliberately

sends a TV crew on a wild goose chase down a bad road that damages their

news van, orcauses them to stand vigil in

the cold for a few days somewhere, under false

pretenses. In egregious situations ... news folks would feel so misused

and abused that they would want charges brought

against the hoaxer, to protect the rest of the ENG community, if nothing else. That's when a broadcaster would take the

time to go through the motions to testify and waste even more time and energy to pursue penalties

and/or compensation.

And if it goes that far ... there should be automatic statutory penalties

from which the news organization can negotiate backwards in seeking compensation,

rather than having to prove actual damages. That's what statutory penalties

are designed for, in part.

The single most effective way to prevent or reduce these situations is to allow news employees (field reportes, news directors, cameramen, etc.) to truthfully mention,

to any informant or tipster, that "There is a

federal law against deceiving news broadcasters. A lot people depend on

our reporting. You can go to jail if you're just trying to pull a hoax

on us. I'm just lettin' you know ..."

That could save a whole lot of wasted time, energy and gas money, as it

surely does for law enforcment and fire fighters.

Legitimate tipsters would not be offended to hear that. They would understand,

fully.

Call to Action

- Are there any existing laws prohibiting hoaxes in this specific context?

The specific language of the proposed statute can and should be hacked out sensibly and openly. The first hurdle is to find out if there are any existing laws, in any legal jurisdictions, of any country, that prohibit hoaxes directed at the news media specifically.

No matter what, the legislative analysis will at least consider similar existing laws, even if they are in foreign countries. If you live outside North America, and you are familiar with the laws of your own country, and you know of a law (which can be a local ordinance) prohibitng news hoaxes, please let us know. Send us an email at CONTACT@BFRO.NET

One of the objectives of the statutory language should be to reduce the burden on broadcasters and government, without creating resistance or burdens in other ways.

Best to begin construction of the statutory language with input from those who write laws for a living. If you know someone in any country who authors laws on a professional basis, please forward the link to this page to that person and ask the person to send us their thoughts on the matter. It could make a difference. You never know.

|