|

If you have any information related to the subject below, please contact

us at Contact@BFRO.net, or join on the BFRO's

free discussion board and mention it there.

The content below describes something that may have been seen before by

humans, but has never been described before in writing, as far as we can

tell. Please do correct us if you can cite a previously published

source describing snow mounds of the same description.

The short description: Wood-debris-covered snow mounds. They are waist-high,

dome-shaped mounds of clean snow, with a layer of wood debris coating

the exterior of the mound. These mounds are noticeably different than

naturally formed snow drifts, and the wood debris layer is not wind-blown

but rather placed by hands.

The Tentative Explanation

These wood-covered snow mounds may have been constructed to preserve

a source of uncontaminated water in the form of virgin snow -- water

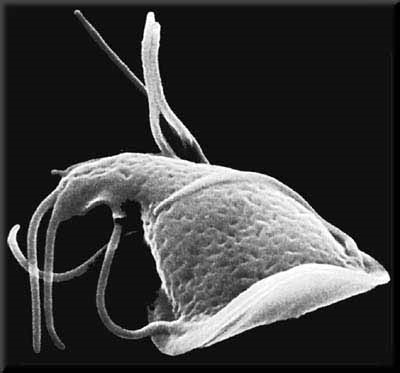

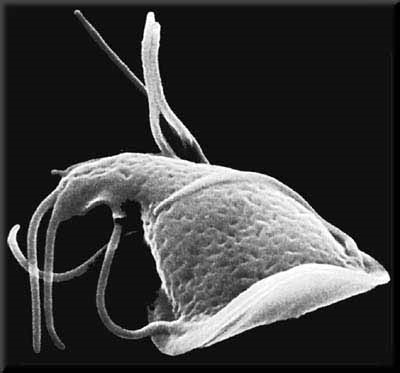

uncontaminated by various bacteria and microorganisms such as Cryptosporidium

and the Giardia

lamblia parasite.

In California's Sierra Nevadas the word "Giardia" sends

chills up and down the spines of cowboys

and hikers. It is a water-borne intestinal parasite found in otherwise

clean pond water and stream water. It causes a dreaded intestinal

illness called giardiasis

(referred to simply as "Giardia").

|

Recent studies have shown that many people who believed they were

stricken with Giardia after drinking untreated mountain water had

actually been infected not by Giardia lamblia but rather a cousin

organism such as Cryptosporidium, which is also found in untreated

Sierra water. There are various types of water-borne organisms in

the Sierras that will cause debilitating giardiasis-like symptoms.

Giardia lamblia occurs naturally, and is found world-wide, but it

has a particularly strong reputation in California's Sierras Nevadas,

where it is said to be in abundance and spread by numerous cattle

operations.

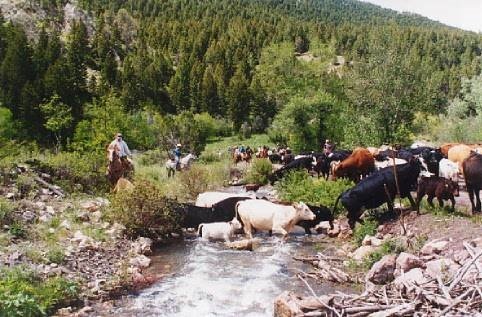

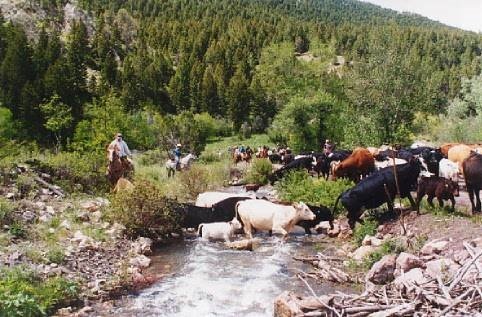

Cowboys have been herding cattle into the Sierra Nevadas

for the past 100 years or so. At this time numerous cattle operations

drive herds of cattle into the high country every year as the snow

recedes. The cattle operations do this to reduce their yearly feed

costs. The cattle feed on lush spring grasses and flowers in the

alpine meadows in the summer, and they generate an abundance of

cow dung around water sources like ponds and steams.

In many places in the high Sierras cow dung is more abundant and

plainly visible than the dung of any other large mammal species.

In the warmer months migratory deer herds, and their attending

predators, frequent the alpine meadows and bogs as well.

When winter rolls around again the cows are herded back down to

the low country. Sometimes cattle herds are transported in both

direction by cattle trucks. Cattle trucks bring in cows from various

places around California.

|

People who live and work in the Sierras and Central Valley say drinking

unpurified mountain water is a dangerous gamble. Some will say a

hiker has a 50/50 chance of ingesting Giardia, or something like

it, when drinking untreated water from any given stream or pond

in the mountains. Others will say the odds are closer to 10%.

Even if the odds are only .05%, a human (or any other primate) will

eventually get Giardia (or something like it) if it frequently

drinks unpurified water from ponds, lakes and streams in the Sierras.

Human primates typically avoid Giardia and similar organisms by

purifying Sierra water before drinking it -- usually by boiling,

or adding iodine pills, or using reverse osmosis filters, etc. Other

animal species cannot purify their water so easily.

Deer and various small mammals can get most of their water

from plants, and by licking the condensation off plants and grass

at night and in the morning hours. Deer don't absolutely need to

get water from ponds or stream water. Herds will often be found

grazing in areas with no ponds or streams nearby, due to this ability

to hydrate from plants and nightly condensation on plants.

Spring water sources emerging from rocky mountain slopes will be

free of Giardia-like microorganisms, but these types of springs

are sparsely scattered, and can only be guaranteed to be Giardia-free

right at the spring source.

A smart, large animal with hands could avoid Giardia (and similar

organisms) by accumulating and preserving piles of virgin snow at

strategic locations as the snow recedes to higher and higher elevations

after winter.

In the Sierras, snow generally accumulates during winter storms.

The major storm events in winter set the lower limits of the snowline,

then the line recedes during the rest of the year, except when occassional

spring storms reset the snowline to a lower elevation temporarily.

The zone just below the receding snowline is also where the most

deer are found in the Sierras.

Like the battles over water rights in California, high country cattle

grazing rights have been a political battle for decades in the state.

The US Forest Service has traditionally been on the side of reducing

and eventually eliminating cattle operations in the Sierras, due

to the various

types of environmental damage they cause, but the cattle operations

are widespread and have been going on for generations.

There are many towns around the base of the Sierras where local

cowboys still earn their main chunk of yearly income by herding

cattle in and out of the high country. The original cowboy families

are steadily disappearing nowdays, but they are being steadily replaced

by lower cost migrant agricultural workers.

Eliminating high country grazing will not eliminate cows and hamburgers,

it will merely make it marginally more expensive for cattle operations

to feed and water herds of cattle in the low country in the warmer

months.

|

We are releasing this information now, following the Fall 2007 Sierras

Expedition (in El Dorado County), because during that expedition we heard

that rangers in yet another part of the Sierras had recently come across

similarly constructed snow mounds, and those rangers were puzzled by them.

The story came to us through a casual conversation with an employee at

a ranger station. The story could not be verified, but the story itself

was enough to encourage us to publish this earlier description, and establish

some historical chronology.

If these specific types of formations have not been documented before,

then we are pretty confident that California State Park Ranger Robert

Leiterman was the first person to examine and describe them. Leiterman

found two of them during a BFRO expedition in June 2005. He wrote an article

about his find shortly after that expedition, but it wasn't published

until now, for various reasons.

We knew if these wood-covered snow mounds were indeed the products of

some non-human animal behavior, then other people would eventually find

some in other places, and we would eventually hear about it through some

channel. By waiting to hear about at least one similar find, before publishing

Leiterman's description, we would be less concerned about human fabrication.

It was an issue we have debated in the past -- what should we release

publicly, and how will that affect future evidence collection for various

types of evidence. People could potentially fabricate these snow mound

formations down the line, but if we don't speak about them publicly ever,

then we won't be able to effectively solicit reports of similar finds.

People can fabricate footprint finds also. But that doesn't deter us from

talking about footprint finds. Over the years we have seen that some footprints

finds will be fake, but other finds will be apparently legitimate, so

better to ask for all footprint finds, knowing that some legitimate footprints

will come forward that way.

Potential Connection with Sasquatches:

Sounds indicative of sasquatches (howls, whoops, knocks and whistles)

were heard in the same area where the mounds were found -- a mountain

valley outside the Emigrant Wilderness -- over the course of a few days.

The mixed rocky terrain was generally not conducive to footprints. The

amount of terrain made it impossible for the expedition group to thoroughly

scour the area, so there may have been more evidence around, but we didn't

find much of it in the course of a few days. We noticed the most obvious

things: the various sounds and these snow mounds.

Sasquatches do not leave much noticeable evidence behind, most

of the time. In non-snowy conditions, the impact sasquatches create in

their forest habitats is mostly indistinguishable from the impact of bears

and other large animals. They can avoid leaving distinct tracks simply

by avoiding exposed dirt, mud and sand wherever possible. Other large

mammals, like mountain lions, will avoid leaving tracks, so it would not

be a stretch for other mammals to exhibit the same behavior.

Sasquatches definitely do not make complicated tools or structures,

by human standards. Occassionally BFROers will find arrangements of natural

objects that appear to have been placed by hand. Although stick formations

are often misinterpreted by people who are looking for sasquatch evidence,

stick formations are occassionaly found which were clearly erected and

positioned by something with hands.

These snow mounds discovered by Leiterman were distinguishable for that

same reason. They were clearly made by something with hands.

There are only two types of animals in North American with large hands

(larger than raccoon hands) -- humans and sasquatches. Determining that

a stick formation was made by hands does not automatically mean it was

made by a sasquatch, but it eliminates almost every other possibility.

The human possibility becomes much less likely depending upon various

factors and circumstances such as seasonal inaccessibility, which was

definitely a factor in this case.

Robert Leiterman's article:

_________________ _____________________________________________________

Robert Leiterman approaches the first mound |

| The location was not far from the boundary of the Emigrant

Wilderness, in the Sierra Nevada Mountains, California (Tuolomne

County). This is the same general area where the "Sierra

Sounds" were recorded. |

"Do they look natural...like the sticks, branches, and snow could have

just fallen in place?" Matt Moneymaker's voice boomed over the walkie-talkie

radio.

"No!" Bart Cutino responded confidently into the walkie-talkie.

Bart looked over to me and smiled. I knew we were thinking the same thing...

This snow mound was not a natural formation. It was built by something

large and with hands.

Matt's voice came over the radio again: "Does it look like a person could

have built it?"

Bart replied .. "Yeah, a person could have done it ... but you should

take a look at this!" Bart's voice reflected my own excitement.

It was getting late and Matt was listening for sounds on a granite outcropping

a considerable distance away. We were losing daylight. He would not be

able to make it to base camp before darkness fell. There was just enough

time for us to show this to others in camp. Matt would have to wait until

tomorrow morning to see what all the fuss was about.

This expedition was Bart Cutino's third BFRO expedition that year. The

June 2005 Sierra Nevada Expedition had been my fifth BFRO related expedition

that year, and I have been a state park ranger for several years. We had

never come upon anything like this mound before, and never heard it described

before.

|

| Robert Leiterman (Fortuna, CA) and Bart Cutino (Monterey, CA) |

We stumbled upon the first mound by chance. Bart was trying to talk me

into heading back to base camp, but I wanted to see the place the topo

map showed as a pond. Several expeditioners had reported hearing sasquatch-like

sounds from this direction on previous days.

While walking around the perimeter of the pond, the first mound caught

my eye. I was saying, "Keep your eyes open for anything unusual, like...like

that big pile of wood chips over there." Then I got curious. It was odd

-- a big pile of wood chips in a dome-shaped mound. Bart and I decided

to have a closer look. That's how we came across them initially.

After trying to get Matt to come take a look, Bart had another idea. "We

should dig it up, or mess it up and set up a trail cam," he said enthusiastically.

"It's our last night. Time to start throwing the ball long."

We wondered if the snow mound was some kind of primitive refrigerator,

and hidden within would be the ultimate prize ... like an animal carcass.

So we wanted to dig into it to see.

At first I had just wanted to leave it alone. I'm not superstitious, but

I'm a ranger. One thing rangers say often to the public is "Take nothing

but pictures, leave nothing but footprints." But we knew we would feel

stupid later on if we didn't have a look inside while we were still there.

Then we noticed a similar mound on the opposite side of the pond. That

really got our attention. We walked around the pond and checked it out.

Same type of mound: a very symmetrical mound of clean, white, unadulterated

snow, topped with wood debris from decaying fir logs and snags. This one

appeared to be more recently constructed.

The second mound found was a larger mound. It was four-feet tall by approximately

eight feet in diameter. The brown, decomposing wood pieces on the mound

varied in sizes. There were some roughly one-foot long, by roughly five

inches in diameter. Those pieces were on the outermost layer, but then

85 percent of the debris pieces contacting the snow were two inches or

less in size.

The whole process of construction appeared to be a lengthy one. It wasn't

just a bunch of wood debris poured onto a mound of snow. There was a process

involved with the placement of the wood pieces. One thing was undeniable

about the placement of the wood pieces: It was done with care.

After taking in this sight for a while, Bart and I ran back to camp and

grabbed a shovel and a trail camera, and a couple of other BFRO investigators

(Dennis Pfohl from Colorado and Dave Johnson from San Francisco) and headed

back to the mound. When they arrived at the larger mound, their facial

expressions said what they were thinking before they both said it out

loud:

"Wow!"

"There's another one over there, a smaller one," I said. "It was

the first one we spotted so let's start over there."

|

| Robert Leiterman and Dave Johnson at the second mound |

Dave stayed at the larger mound while the rest of us made our way around

the edge of the pond. We knew it was important to do this before we started

disturbing it, because there was a possibility that the mound was created

for symbolic purposes, like as markers of some sort. We wanted to see

how visible they were from a distance.

I looked over at the larger mound across the pond and saw Dave's tall

figure with hands on his hips, staring down at the mound. I could see

it in his posture. He was running down a list of possible explanations.

Dave Johnson has three university degrees and can figure out perplexing

problems faster than most people. It was good to see him standing there

pondering this for a while, trying to figure it out. Clearly it stumped

him as much as us, which made us a bit more excited.

We saw lots of deer sign all around the soft, moist soil of the pond.

The clear water of the pond was alive with caddisfly larva, dragging their

shell-like structures across the muddy, organic bottom. The water striders

skated across the water's clear surface. It was a healthy pond.

We noticed some fresh boot prints in some exposed soil in a boggy portion

of the pond. The path taken by the booted individual skirted along the

edge of the pond in one area. Evidently, the day before, a member of the

expedition had walked by here. He walked along part of the pond but his

trackway went nowhere near the mounds. Later on we confirmed that it was

a member of our own party. He said he did not noticed the mounds near

the pond when he walked through there the day before.

The previous winter had been an unusually cold and wet winter. The last

of the snows had hit the area during the beginning of June. Record snows

had been recorded in May (2005). The area was not accessible by wheeled

vehicles at all when the older of the two mounds was constructed.

|

One of the mounds, the larger mound, was likely built within a few days

prior to our arrival. The smaller mound was buillt a few weeks

prior to that. This was notable for us because the gates to this section

of the forest were opened by the Forest Service during the course of the

expedition, after the snow had sufficiently melted to allow vehicle access.

We all knew the mounds could not have been made by someone setting us

up for a practical joke because one was built long before we decided to

look around in this particular area. The gates had been closed when we

first arrived in the zone. We subsequently decided to enter that particular

area once we heard the gates had been opened.

The expedition party had been searching around at a lower elevation on

previous days and decided to check out this area on a whim in order to

listen for sounds. Knocks were reported by some expeditioners within 24

hours of camping in that valley. These reports drew more of the expeditioners

up to that elevation. Various other sounds were heard after that by more

people which encouraged the expeditioners to focus on this particular

area for the rest of the trip.

Due to the challenging difficulties of entering this large area while

it was still snowed-in, we surmised that the only realistic possibility

for human origin would be the snowmobiler scenario: if a human(s) had

snowmobiled (or used snowshoes or cross-country skis) into the area while

it was under snow and then spent many hours building and preparing these

mounds ... for no apparent reason. The mounds were too small to be used

for snow shelters for humans and there were no entrance tunnels of any

sort. And human snow shelters are not normally constructed with a layer

of wood chips on top. Some elaborate snow shelters are made with wood

frames and light branch material weaved in, but this was very different.

Everyone who came from base camp to see the mounds observantly circled

them, examined them on all sides, and looked closely for any clues of

an entrance tunnel. At least seven people eventually hiked over to look

at the mounds -- each one of them thinking, while en route, that he/she

might solve the mystery with a logical explanation. There were all stumped

when they arrived. The snow shelter idea melted away quickly when the

newcomers examined the mounds themselves. Everyone looked for clues of

human purpose or involvement but no clues were found. It was conceivable

that a recreational visitor built these two mounds, while the area was

still under snow, but there were no indicators for it. There should have

been some clues of human involvement on or around the mounds, like

marks in the snow from a snow shovel, or boot prints, or hand prints,

etc. There were none.

When we reached over to touch the wood chips on the top of the larger

mound (larger in diameter) we nearly fell onto the mound because of how

much we had to lean over. Whereas, the mound maker apparently did not

have to brace itself against the mounds throughout the whole process of

building it. Nor did it have to stand on the mounds while buidling them,

as we would have done in order to stay properly balanced. It seemed that

the mound maker had a very long reach.

The smaller mound was erected beside a stump -- not over a stump,

but rather along side a stump. That mound had melted back from the stump

a bit but it was still a nice symmetrical mound piled high with snow,

complete with a topping of dry heartwood debris. The heartwood topping

was collected from the same decaying deadfall tree several meters away.

It was not debris from the nearby stump. There was a bread crumb trail

of spilled wood chip debris between the decaying deadfall and both mounds,

showing that the debris came primarilly from the same rotting deadfall

log.

The wood didn't cover every square inch of the smaller mound, as it so

carefully did on the larger mound. Either it wasn't constructed with as

much care, or part of the topping had sluffed away in places, exposing

the snow beneath.

We looked at the smaller one carefully. We felt confident that it was

older than the larger one across the pond. Both of the mounds were under

the partial shade of fir trees from above, and in the shadow of mountain's

morning sun. But the smaller mound had a lot more shade cover than the

larger mound. Even so, the smaller mound had clearly melted back a bit

from it is original shape.

The wood debris topping was composed of fir bark and fir heartwood. The

deadfall log source was much closer to the large, fresher mound. The smaller

mound was on the other side of the pond from the source of the wood debris.

Whatever had built the smaller mound had to carry the bark and heartwood

all the way over to the other side of the pond. It would have been very

consuming to do this, and required several trips around the pond. Whereas

the larger, fresher mound was roughly 25 feet from deadfall log from which

all the debris came from. It was as if the mound builder decided to build

the second mound much closer to the selected debris source and thereby

cut the effort level in half.

After examining the smaller mound we worked our way back to the larger

mound. We stood around staring at it for a while as we debated our next

action and whether we should dig into it. We all thought it might serve

as a refrigeration structure. We joked that we might find a wide assortment

of dead animals inside. We briefly mentioned the impact it would have

on this type of research if indeed there was any kind of food stashed

inside.

Digging into the Mounds for a Look

During the excavation of the mound we noticed more subtleties. We removed

sections of the organic debris from outside of the mound. The outside

surface was smooth and glazed over as if it was rubbed by hand. The edges

of the larger pieces of decaying heartwood had left edge impressions in

the ice surface. It could have been caused when the pieces were slapped

hard onto the mound. It was also possible that some wood pieces had collected

heat during the day and had begun melting into the icy surface.

We started about halfway down the sides of the larger mound and excavated

three tunnels into the heart of the mound. We dug from opposite sides

towards the middle and then down to the ground. We did not find anything

but clean snow the whole way through.

Before leaving the area, Dave, Bart and Robert set up a motion-triggered

trail camera, with the hopes that the mound builder would revisit the

mound.

The photo below was taken approximately three weeks later when Dave Johnson

went to check the camera at the second mound. By that point the snow had

melted completely and left behind the layer of wood debris.

The mounds were not snow accumulating on a stump. Notice there is no stump

in the photo below.

The trail camera was removed from the area because it was cumbersome to

service repeatedly. The location was a long drive for all the people who

were willing to help. We also felt it was unlikley that new snow mounds

would be built at those same spots next Spring. The odds seemed pretty low

for that, after we had conspicously altered both mounds in our effort to

figure out their purpose and origin.

Everyone who saw the mounds in person was initially puzzled by them. They

required so much effort to assemble that there must have been a compelling

need to assemble them. In trying to understand the needs at play,

human needs or sasquatch needs, I considered Abraham Maslow's Hierarchy

of Needs.

In the middle of the last century a man named Abraham Maslow developed a

theory that humans are worked upon by forces, and that our basic needs are

instinctive. He broke them down into five basic prioritized needs.

1. Physiological Needs: Biological - food, water warmth and air to breath.

2. Safety Needs: After satisfying the needs of number one, then comes security

and shelter.

3. Need of love, affection and belonging: After satisfying the needs of

number two, then comes time with others.

4. Needs for esteem: After satisfying the needs of number three, then comes

self-respect and respect for others.

5. Needs for Self-Actualization: After satisfying the needs of number four,

then comes do what you are "born to do". Writers write, painters paint,

and bigfooters try to have encounters with bigfoots.

The further down the list one goes, the more esoteric and distinctly human

the needs become, and thus the more potentially divergent from the needs

of an ape species with a different lifestyle.

Could a sasquatch have some esoteric needs that a human might not be able

to understand or appreciate? ... esoteric needs powerful enough to inspire

it to build these snow mounds for no practical purpose?

Yes, potentially, but the lifestyle of a wild ape would likely be more practical

and basic than a human lifestyle, especially so in a cold environment. In

a cold environment, the bulk of a wild ape's nutrients, caloric energy and

daily routine would necessarily be directed to the pursuit and acquisition

of more nutrients and caloric energy. Caloric energy and nutrients would

be its money, in a sense, and the pursuit of money would be its business.

A successful business-ape would be trying to conserve its money as much

as possible, and it would learn to avoid things that might interfere with

its business.

If these snow mounds somehow helped the business both ways -- helped it

to acquire more nutrients and caloric energy, and helped it avoid things

that mght interfere with that pursuit, then the expenditure of so much caloric

energy, assembling these snow mounds, would be understandable and economical.

Other scenarios were considered at the scene, that afternoon, which compelled

us to look for physical clues for those scenarios in the general vicinity.

Q: Could the snow mounds have been built for a future use, like for storage

of prey animals not yet acquired?

A: It's possible, but it is unlikely, because there are bears in the Sierras.

Stashing any kind of meat in melting snow is not going to prevent bears

from smelling the meat and taking it. When there are bears in a given

area, the storage of any sizeable quantities of fresh meat (outside

a metal box) is basically a gift to the bears.

Q: Could a forest service employee have done this?

A: Not likely, because way too much time and trouble went into these mounds.

It would have taken hours to do, for no apparent reason. Also, there were

no clues near these mounds that indicated human activity or traffic. If

this had been a construction site, of sorts, the ground would have been

more disturbed --disturbed in characteristically human ways.

Q: Could it have been a practical joke directed at the expedition?

A: Not likely, for a few reasons: 1) This mountain valley was basically

inaccessible to anyone but snow-shoers when both mounds were built. 2)

We didn't even know that we would end up in this specific valley until

a few days before we went there. One of the mounds pre-dated the decision

to go there by at least two weeks.

Q: Could it be an 'exploded cedar stump'?

A: Definitely not. The mounds were comprised of pure white snow with a

layer of wood debris on top. If it was an 'exploded cedar stump' the snow

would be on top of the wood debris, not the other way around. Also, there

would be remnants of a stump and roots below it. There were no remnants

of a stump under either mound, as was verified weeks later after the mounds

had melted away completely. The source of the wood debris was a rotting

deadfall log.

Q: Were these mounds built to store a source of clean water?

A: The mounds were within a few feet of a relatively clear, clean pond,

and only a few hundred feet from a year-round cascading mountain creek.

The pond water appeared to be clean enough to drink. There were many insects

around the pond, and it was full of larvae, which is normally an indication

of clean water.

In the Sierra Nevadas, however, people are strongly warned against drinking

apparently clean water from streams or ponds, because Sierra water has

more than its fair share of Giardia

lamblia parasites, which can make any animal or human dreadfully ill

with giardiasis.

Giardia parasites could be in the pond or the creek, but would not be

present in fresh clean snow.

Many of us in the organization know people who have suffered from giardiasis.

Those people will go to great lengths to purify their drinking water in

the mountains, to avoid getting giardiasis again. A severe intestinal

illness would definitely interfere with a wild ape's career -- the pursuit

of nutrients and caloric energy.

Reserves of clean water would help the ape avoid a sickness that

is not only uncomfortable, but also physicaly debilitating. Dispersed,

clean reserves like these snow mounds would be particularly critical

for an ape species that must follow wandering herds of deer.

The Question of Immunity to Giardia:

Q: Could a wild ape species develop a physiological immunity to Giardia

Lamblia parasites?

A: Acquired resistance to Giardia in mammals is not

well understood, but one thing is clear about it -- a mammal's adaption

and resistance to Giardia develops as a consequence of prior infections.

Any mammal would get sick from Giardia a few times, at least, before its

physiology would adapt enough to reduce the symptoms of another infection.

Resistance to Giardia infection involves changes to the lining of the

intestine and thicker mucosal secretions, among other things. These changes

make life more difficult for the parasite, and eventually help limit and

purge the infection, but they would not prevent the host animal from getting

infected to some degree, initially.

The analysis above focuses perhaps too much attention on Giardia Lambilia.

It needs to be re-emphasized that there are an array of water-borne fecal-to-oral

microbes in the Sierras (parasites, viruses, and bacteria that can cause

similar types of sickness and diarrhea) which are brought into the Sierra

high county by alpine cattle operations after the snow melt, and all those

microbes flow downhill.

If you stumble across something that looks like the snow mounds described

and pictured above, please photograph it as soon as possible, before it

melts, and then please contact us at Contact@BFRO.net to let us know.

If you would like to discuss these formations with the folks who found them,

please join the BFRO's

free discussion board.

|